ProBlogger: NEVER SAY NEVER: Do You Always Have to Follow Writing “Rules” to Be a Successful Blogger? | |

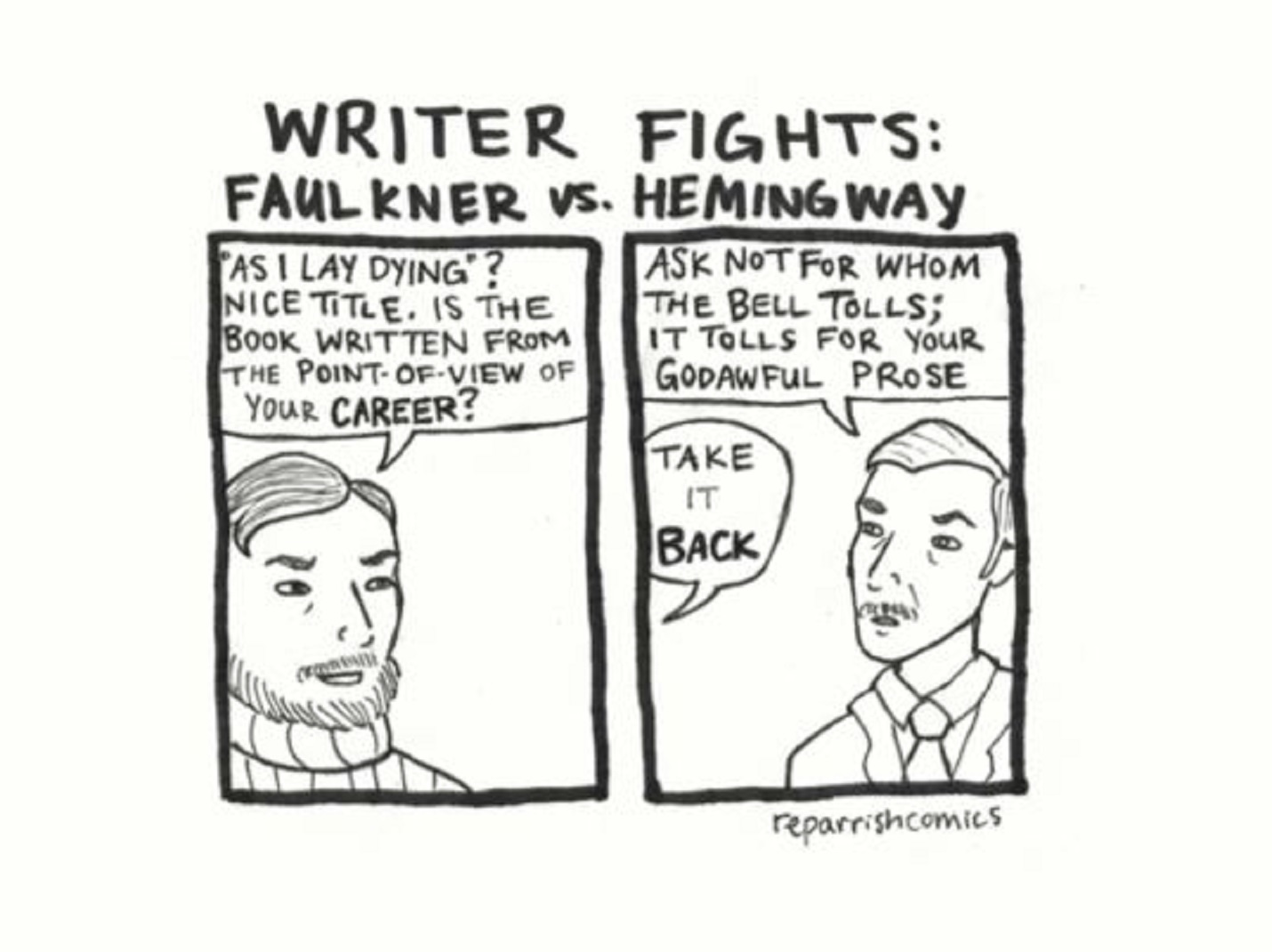

| NEVER SAY NEVER: Do You Always Have to Follow Writing “Rules” to Be a Successful Blogger? Posted: 14 Sep 2016 07:00 AM PDT This is a guest contribution from author Daryl Rothman. "Never," exhorts George Orwell in his prolific essay Politics and the English Language, "use a long word where a short word will do." This etymological edict claims many adherents, and who amongst us has not wrestled with that great literary conundrum of word choice? Whether you blog, pen fiction, nonfiction or anything at all, finding the right words and writing style is essential. But how to do it? And are these rules written in stone? THE GREAT DEBATEWilliam Faulkner might have said no, especially in light of an exchange he once shared with Ernest Hemingway. Their relationship was freighted at turns with rivalry and respect, and some believe Faulkner intended no malice when he said pointedly of his fellow Nobel Prize winner: "he has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary." But there would be no farewell to arms, as Hemingway fired back: "Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don't know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use."  Reprinted with permission of RE Parrish RULES OF ENGAGEMENTTheir sometimes salty repartee underscores rather famously the fuss (or am I better to say, hullaballoo, or perhaps rumpus) over Orwell's entreaty. Hemingway and myriad others have shown convincingly that size isn't everything, that simpler can be better, but the question doth remain, is it always? Let's return to Mr. Faulkner. Consider this passage from As I Lay Dying: "How do our lives ravel out into the no-wind, no-sound, the weary gestures wearily recapitulant: echoes of old compulsions with no-hand on no-string: in sunset we fall into furious attitudes, dead gestures of dolls." Now what was it Mr. Orwell said? Never use a long word when a short word will do? Well then. Lovely as the above passage is, perhaps it would stand in even loftier esteem were we to adhere the great rule. Let's give it a shot:

Well, not too bad, uh? Has its moments. Not quite so good as the original, I'd say, but still. But let's try another. Cormac McCarthy, The Road.

Goodness, that's something of a doozy. Let's see if we can clean it up a spot.

Better? I mean, come on, torsional? Um, yeah. Torsional. And only that. And quite possibly only McCarthy could write it, right there and right then, perfectly. I remember first reading that passage years ago and thinking, wow, I'd have never thought of that but how very perfect indeed. Same with wimpled. I remembered catching a rainbow trout in a river in Colorado and how it looked and felt and so there again, when I read that it resonated flawlessly. But maybe that's me. And that's very much the point. FINDING THE RIGHT WORDSI remember the dry comedian Steven Wright quipping: "I've written several children's books—but not on purpose." I am rather disinclined to tender a dispatch to Mr. McCarthy imploring him to kindly dumb things down. Of course, the Hemingways, O'Connors, and so many others have more than demonstrated the power of a more spare approach to prose (not that they haven't produced their share of elegant, lyrical, and yes, longer passages too). One should not impugn good, crisp, leaner writing as in fact dumbed down, for sometimes, perhaps even often, Hemingway is right. Simple can be better, more potent in their sparsity. Consider this passage from his fabled short, The Snows of Kilimanjaro: "He was going to sleep a little while. He lay still and death was not there. It must have gone around another street. It went in pairs, on bicycles, and moved absolutely silently on the pavements." Not bad at all, I think we'd say. No wimpled or vermiculate yet just as strong in its way, in what it says and what it doesn't, and in the efficient yet still depthful manner of its crafting. And the depth of the moment the subject—looming death—is best served by this unvarnished presentation. Of course, there is a bit more going on there, too. A wonderful bit of personification, death "not there" yet close, just around the corner, pedaling on "another street." Yet surely to return. This is not said and there again, the power of saying something simply, or not at all. He didn't need to go all McCarthy, nor McCarthy all Hemingway. The best writers find the best words, and the best words adhere no preordained styles or rules. And permit me here a brief caveat. While clearly I am rejecting the notion of tendering Orwell an obedient "will do," that very portion of his counsel warrant fair consideration. Never use a long word where a short word will do. Not, when a short word is available (for one almost certainly is). Will do. Will suffice, or perhaps even, do better. But even through the context of that lens, we are left with the same charge: determining, in fact, what will do better and, in fact, what will do best. And neither Orwell nor anyone can answer that in advance. A BALANCING ACTHarvard’s Dr. Stephen Pinker—one of Time's 100 Most Influential People in the World, and an esteemed linguist, author, psychologist and cognitive scientist—addresses in his book The Sense of Style Orwell's admonition. Pinker, who serves as Chair of the Usage Panel of The American Heritage Dictionary, acknowledges that floridity for its own sake is by no means desirable (“showing off with fancy words you barely understand can make you look pompous and occasionally ridiculous”), yet also reminds us it doesn’t have to be one or the other. Noting that many studies on quality writing cite the utility of a varied vocabulary replete with some surprising words, he stresses that “a skilled writer can enliven and sometimes electrify her prose with the judicious insertion of a surprising word.” I concur with all of this, maybe most of all the support of mixing things up a bit. A quick return to the McCarthy passage is case in point–consider these successive sentences: On their backs were vermiculate patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming. Maps and mazes. The first is a longer, lyrical sentence headlines by a somewhat unusual, or at least less common word, vermiculate. The next sentence is short, crisp, each word simple. And it works, this ebb and flow, this variety: it works in this passage, throughout the book, and for any writer committed and skilled enough to artfully employ it. Some of the reasons for that go even deeper, Pinker says. "The best words," writes Pinker, "not only pinpoint an idea better than any alternative but echo it in their sound and articulation, a phenomenon called phonesthetics". The lesson once more: sometimes simpler is better, sometimes not, and it doesn't hurt to mix it up a bit. My first novel was Young Adult/Fantasy and I was preoccupied with finding the right balance between challenging young readers yet not turning them off by compelling too many trips to the dictionary. But some of that, argues Pinker (and this was always my inclination), is not such a bad thing. "Readers who want to become writers should read with dictionary at hand," he writes. I certainly always do, viewing it as my readerly responsibility to be up to the level of the scribe. If the prose ultimately emerges as too stuffy or florid or freighted with finery for the mere sake of it, then I'll put it down soon enough anyway. That's just business. But "writers should not hesitate," Pinker continues, "to send their readers (to the dictionary) if the word is dead-on in meaning, evocative in sound, and not so obscure that the reader will never see it again." The writerly responsibility. And so it goes. I had the good fortune to see Dr. Pinker last year when he was in town for a speaking engagement, and he has been kind enough to respond to my occasional correspondence since. I told him how I bristled at the frequent exhortation toward blind adherence of these dictates, particularly the "long word/short word" one, and I was grateful for his response and commiseration. "I tend to agree," he told me, "that the puritanical advice on avoiding unusual words in classic style manuals (a reaction to florid, over-wordy Victorian styles) is overdone, and that rare words can enliven prose." SO WHAT TO DO?It's simple. (No, really.) Never say never. I remember a friend in my MSW program years ago lecturing me that I could not start a sentence in the Op-Ed piece I was writing with a conjunction. "You can't begin a sentence with and," she wrote. I knew this was the standard grammatical "rule" of course, but this was not an essay, it was an opinion piece, with a slightly more conversational tone. And sometimes we need to adjust our prose to tone or subject or audience at hand (or even break the rules and begin with a conjunction, as I have done here). I write fiction so that's what I've touched on here but I also write articles and posts—to wit—and blog, like many of you, and it is essential that we in fact consider these factors—tone, subject, audience, desired effect—in our writing. Are you blogging about a serious topic, or light? Are you writing for a highly-educated audience? Is there a call to action you want your readers to embrace? There are myriad instructive articles such as this one geared toward bloggers and anyone writing to persuade or even sell. Again, I would only caution against accepting on faith any rules or secrets or magic bullets because at the end of the day there is simply no one size fits all. For those of you who also pen fiction I would consider you word choice against the nature of your story itself, and its characters. A raw tale of raw and hard-edged characters garnished throughout with gaudy prose may reek of pretension, or at the very least, incongruity. Now, it's possible to pull it off. Editors have instructed me that if the characters wouldn't think like that or speak like that, I shouldn't write like that, and this is oftentimes sage wisdom. Oftentimes, not always. Again, McCarthy. I could probably count on one hand individuals who think or speak like he writes—and maybe Judge Holden but otherwise few if any of his own characters—yet still, it works. Never say never. There's only one McCarthy, granted, so adherence to some of the long-standing rules may in fact anchor many of us mere mortals, but the point is, it can be done. Rules can be broken, if there is a good reason, and it is done well. Rules can anchor us but also constrain us. Render us hesitant and insecure. Throw off your literary shackles, friends, and write free. You're gonna edit anyway. And shoot, if you're worried about floridity, you can always run things through that Hemingway app they came up with a few years ago (and which Hemingway himself, they said, wouldn't always rate highly on). Rules be damned, at least for your first drafts. As Pinker writes, many of them are rooted not in sound logic but superstition anyway. Write with confidence, take some chances. Write what's right, and no one knows that better than you. WHAT DO YOU THINK?We are a literary community, and I'd love to hear from you. Do you struggle with finding the right words, or worrying about rules? Have you discovered that elusive balance? Please share your questions, and your wisdom. Thank you, and write on! Daryl Rothman's debut novel The Awakening of David Rose was published in 2016, he has written for a variety of esteemed publications and he'd love you to visit him on Twitter, Linked In , Google + , Facebook or his website. The post NEVER SAY NEVER: Do You Always Have to Follow Writing “Rules” to Be a Successful Blogger? appeared first on ProBlogger. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from ProBlogger. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment